|

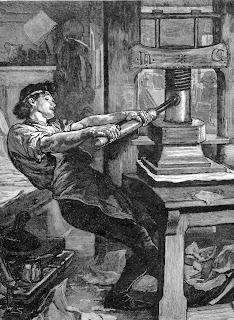

| Gutenberg at his press |

With this new demand for realism came a demand for a

genre of literature that was able to properly convey this realism. In referring

to Defoe and Richardson, two of the first English novelists, Watt says, “Their

basically realistic intentions, of course, required something very different from

the accepted modes of literary prose. It is true that the movement towards

clear and easy prose in the late seventeenth century had done much to produce a

mode of expression much better adapted to the realistic novel than had been

available before” (29).

Another factor that contributed to the rise of the

novel was the rising middle class. In 1696, half of the population of England

lived on “£6 to £20 per annum per family” (Watt 40). The rise of circulating

libraries granted poorer citizens access to books at lower rates, but it was

still primarily the middle class that did most of the reading, being free from

the physical labor and lack of education found in the lower classes, and also

free of the social demands found in the upper classes. Not only did the middle

class have the money to afford books, but they also had the leisure time to

enjoy the books as well.

|

| The Age of Reason |

The novel soon became very popular, and, as Nancy

Armstrong wrote:

While Armstrong is referring mainly to female

readers, the idea rings true for all readers as they were able to steep

themselves in a story that, being a mix of realism and fiction, provided a

reprieve from the cares of everyday life.

In addition to the appeal for readers, the novel

offered a similar escape and new horizon for authors:

As technological advances changed the face of society, they also changed the face of literature as more people had time and money to devote to reading. This also encouraged writers and gave them a new field to experiment with. In reference to Jane Austen, Nancy Armstrong wrote, “Austen’s novels striv[e] to empower a new class of people—not powerful people, but normal people—whose ability to interpret human behavior qualifies them to regulate the conduct of daily life and reproduce their form of individuality in and through writing” (136). Literature not only impacted the economy and the artistic scene, but also the ideological scene as ideas were exchanged and reinforced through not only what was being written, but by who was writing it. Authors also took the opportunity to pass along moral wisdom. Armstrong borrows this anecdote from Darwin:

Novels became an in-depth medium for inexperienced

people to become acquainted with human nature. As Anthony Trollope argued, “No

man actually turns to a novel for a definition of honour, nor a woman for that

of modesty; but it is from the pages of novels that men and women obtain

guidance both as to honour and modesty” (Maitzen 279).

The technology of the time drastically changed the

shape of the 18th and 19th centuries in England, and indeed

these eras are defined by the presence of the novel. Technology would again

introduce a change to the literary field with the modernism movement. As new

and horrific means of warfare were developed, and life made much less sense,

the modernists channeled this confusion into experimentation with the novel,

along with other genres. Works from authors such as Virginia Woolf and James

Joyce pushed the boundaries of the written form of the novel, while remaining

dedicated to the book itself. In regard to the limitations and possibilities associated with the book format, Glyn White quotes Hugh Kenner:

Now at the beginning of a new century, there are more technological advances that threaten (or promise, depending on your point of view) to change the face of the novel once again. I will go into more detail on the next tab, The Experiment, but the main point of this history that I want to convey is that the novel and technology are intrinsically intertwined. Without scientific advances, the novel would never have come into existence, and in its early beginnings, it was considered a radical and unreliable variance of trusted literary forms. However, the novel was able to accomplish something that previous genres had never been able to in its exploration of form and subject.

No comments:

Post a Comment